什么是电子音乐(1)

電子音樂[编辑]

Electronic music ]

维基百科,自由的百科全书

Wikipedia, a free encyclopedia.

(重定向自电子音乐)

(Redirected from Electronic music )

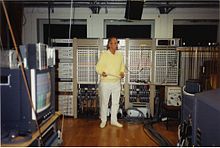

現代化電子音樂工作室(1998年)

Modern electronic music studio (1998)

電子音樂,亦簡稱電音,是使用電子樂器以及電子音樂技術來製作的音樂;而創作或表演這類音樂的音樂家則稱為電子音樂家。一般而言,使用電子機械技術與使用電子技術製作的聲音是可以區別的。[1]使用電子機械製造聲音的設備有電傳簧風琴、漢門式電風琴與電吉他;而純粹的電子聲音製造設備則有特雷門、聲音合成器與電腦。[2]

Music , also known as , is made with , and music made with ; musicians who create or perform such music are called .

電子音樂一度幾乎完全與西方,特別是歐洲的藝術音樂連結,但自從1960年代晚期以後,因爲摩爾定律造就了可負擔的起的音樂科技,意味著使用電子方式製作音樂變的越來越在各國不同區域流行的領域普及與發揚起來。[3]今日的電子音樂包含各式各樣以及範圍從實驗藝術音樂到流行形式如電子舞曲。

Electronic music was once almost entirely connected to Western, especially European, artistic music, but since the late 1960s, the creation of affordable music technology as a result of Moore's laws has meant that the use of electronic means to make music changes is becoming more widespread and popular in different regions of the country. Today's electronic music consists of a variety of types and ranges from experimental art music to popular forms such as electronic dance.

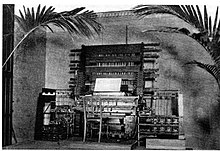

電傳樂器,泰岱斯·卡希爾,1897

Telephonic instruments,

紀錄聲音的能力常被連結到電子音樂的產生,但不是絕對必要。最早的聲音記錄裝置是1857年由法國人愛德華-里昂·史考特·迪馬丁維爾(Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville)註冊專利的聲波記錄儀(phonautograph)。它外表上可以記錄聲音,但是無法回放。[4] The ability to record sounds is often linked to the creation of electronic music, but it is not absolutely necessary. The first sound recording device was a proprietary voice recorder (ponoutograph) registered by the French in 1857 by Edward León and Middot; Scott and Middot; DiMattinville; Douard-Lé on Scott de Martinville. The sound can be recorded on the outside but it cannot be returned. 1876年,工程師耶里夏·葛雷(Elisha Gray)發表了電子機械震盪器的專利。這個「音樂電報」由他於電話科技的實驗以及早期尚存的電子聲音製作的專利演變出。這個震盪器由亞歷山大·格拉漢姆·貝爾為早期的電話延伸出來。1878年,湯瑪斯·愛迪生由此震盪器進一步發展出留聲機,跟史考特的裝置類似,都使用了活塞。雖然活塞繼續被使用一段時間,1887年愛米爾·貝利納發展出了碟式的留聲機。[5]李·德富雷斯特於1906年的發明——3極真空管在之後的電子音樂有深刻的效果。它是第一個熱電子閥或者稱真空管,導致電路可以創造且放大音樂訊號、放送廣播波形、計算數值,並且進行其他各種功能。 In 1876, engineer Jerisha & Middot; engineer Elisha Gray published a patent for electromechanical shockers. The Music Telegraph was extended by his experiments in . This convulsioner was developed by was extended by early telephones; 1878, Thomas & Midot; Edison from which the seismator developed > 在電子音樂以前,作曲家們對於使用科技創作新興音樂有著逐漸增加的期望。一些儀器使用電子機械設計來創造出並且鋪陳出之後電子樂器的興起。一個叫做電傳簧風琴的電子機械儀器於1898年至1912年由泰岱斯·卡希爾發展出。然而,因為它巨大體積所造成的不便阻礙了它被大量採用機會。最常被提及的一項早期電子樂器為特雷門,由李昂·特雷門教授於1919年至1920年發明,是以手控制無線電波來製造聲音。[6]其他早期的電子儀器包括1915年由李·德富雷斯特發明的三極真空管鋼琴;[7][8]1926年由尼可萊·歐布科夫發明的十字發聲器;以及1926年法國人莫里斯·馬特諾發明的馬特諾音波琴,後者被法國作曲家奧立佛·梅湘使用於知名的愛之交響曲,以及他之後的作品當中。馬特諾音波琴還被安德烈·若利韋等其他主要的法國作曲家們所採用。[9] Before the e-music, composers have a growing expectation of new music using technology. Some instruments have been designed to create and post-exploit with electromechanical devices. One of the most frequently mentioned electronic instruments is electro-mechanics from 1898 to 1912 by , 1907年,也就是三極真空管發明後的一年,意大利鋼琴家及作曲家費盧西奧·布索尼出版了《音樂新美感的描述》(Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music),裡頭討論到電子及其他新聲源在未來音樂的應用。他寫到未來在音樂的調微音調尺度,可能被卡希爾的電傳裝置加以實現:「只有長期而仔細的系列實驗,以及持續的對耳朵加以訓練,才能在將來的世代以其藝術裡,令這種不熟悉的素材變成可達成且可塑造。」[10] In 1907, a year after the advent of a three-dimensional vacuum, Italian pianist and composer Philucio· 布索尼在《音樂新美感的描述》中也陳述: Busoni also states in The Description of the New Fancy of Music: 音樂作為一種藝術,即我們常稱的西方音樂,已經幾乎有400年的古老歷史;目前仍處於一種發展狀態,可能是超越現今概念的最初發展,然而我們談論「古典」以及「神聖的傳統」,卻已經有很長一段時間了! Music as an art, what we commonly call Western music, is almost 400 years old; it is still in a state of development that may have gone beyond the original development of today's concepts, but we've been talking about classics and sacred traditions for a long time. 我們有著公式化的規矩,指定的原則,嚴格發號施令;……我們用這些規則培育一無所知的孩子! We have formulaic rules, prescribed principles, strict orders; we use these rules to nurture children who know nothing! 如此年轻的孩子,已足以令人察覺其擁有耀眼的特質,這特質令其明顯超越所有的姐姐。制訂規則者將看不見這非凡的特質,免得他們的規則被丟入風中。這孩子漂浮在空中!並非以腳接觸地面,不知道萬有引力定律,近乎無形。其材質透明,是能發出聲響的空氣,幾乎就是大自然本身。它是——自由的! Such a young child is enough to be seen as having a bright quality that clearly transcends all sisterhood. Those who make the rules will not see the extraordinary quality, lest their rules be thrown into the wind. The child floats in the air, not by foot, and knows not the law of gravity, but nearness. The material is transparent, the air that makes a sound, and it is almost nature itself. It is free. 然而自由是人類從未完全體會的東西,從未完整實現。他們也未能識別或承認。 However, freedom is something that humans have never fully understood and that has never been fully realized. Nor have they been able to recognize or acknowledge. 他們否認這孩子的任務;他們令其背負沉重壓力。這個有活力的傢伙必須體面的走路,就像其他人一樣。可能幾乎不被允許跳躍——但他將娛快地跟隨彩虹的的軌跡,並且利用雲朵來切開太陽的光線。[11] They deny the child's task; they put heavy pressure on his back. This man must walk with dignity, like everyone else. He may hardly be allowed to jump, but he will follow the rainbow with pleasure, and he will use the clouds to cut the sun's light. [11] 經由此一著作,以及個人的直接接觸,布索尼深深地影響了許多音樂家及作曲家。可能是他最著名的弟子埃德加·瓦雷兹就說道: As a result of this work and direct personal contact, Busoni deeply affected many musicians and composers. Perhaps his most famous disciple Edgar & Middot; Varez said: 我們在一起討論未來世界會有什麼樣的音樂方向,甚至,是否應該繼續受到調音系統的約束。他(布索尼)哀嘆他自己的鍵盤樂器讓我們的耳朵調適成只能接受自然界無限多聲音階層中的極小部分。他對我們剛知道的電子樂器非常有興趣,記得特別清礎的是當他讀到電傳簧風琴那一刻。經由他的各種著作,我們可以發現對於未來音樂的預測已經一次又一次成真。事實上,幾乎沒有一項發展他沒預測到,例如這個極不尋常的預言:「我幾乎認為在這新的偉大音樂裡,機器也將會變得必要,並且會在裡頭分配到一定的角色。也許,工業也是,將會在藝術境界的提昇上佔有一定的地位。」[12] We talked about the future of the music, and even whether we should continue to be bound by the sound system. He lamented that his own keyboard instrument had made our ears fit only to the smallest part of the natural multisounding class. He was very interested in the electronic instruments that we just knew, remembering that when he read the tether, we could find that the predictions of the future music had come true again and again by his writings. In fact, there was hardly one development that he had not predicted, such as this extraordinary prediction: "I almost thought that in this new great music, the machine would also become necessary and would be assigned a role in it. 在義大利,未來派藝術家以另一角度來達成音樂美學的改變。未來派藝術家哲學中的一個主要信念是珍視「噪音」,並且將之前沒有被考慮,甚至離音樂性有點遙遠的聲音藝術和表現價值置放進來。巴利拉·普拉特拉在其著作《未來音樂的技術宣言》(1911年)中陳述到他們的信條是:「展示民眾、大工廠、鐵路、大西洋客輪、戰艦、汽車及飛機的藝術靈魂。將機器以及電子的勝利王國領域加入音樂史詩的偉大中央主題。」[13] One of the main beliefs of future artists' philosophy is to value "noise" and to put in place sound art and performance values that were not previously taken into account, even a little remote from music.

1913年3月11日,未來派藝術家路易吉·盧梭羅將他的宣言《噪音的藝術》出版。1914年4月21日,他在米蘭舉辦第一次的「噪音的藝術」音樂會。其中使用到他的吟誦躁音(Intonarumori),據盧梭羅自己表示為「聲學的噪音儀器,其聲音(怒吼、呼嘯、攪亂、汩汩水聲等……)由人手啟動,並且經由喇叭跟話筒來投射。」[14]6月,他在巴黎舉辦了幾場類似的音樂會。 On March 11, 1913, the future artist /a> published his statement, The Art of Noise. On April 21, 1914, he held his first "Noise Art" concert in Milan . Using his voice, Intonarumori, according to Rousseau himself, the sound of his voice (roar, squeezing, chaos, squeezing, etc.) was activated and dropped by a speaker. June, he held several such concerts in Paris . 這十年帶來了大量的早期電子樂器,以及第一次使用電子樂器作曲。第一部電子樂器稱為以太發聲器(Etherophone),是李昂·特雷門(出生時叫列夫·特雷門)於1919至1920年間在列寧格勒創造出來,後來重命名為特雷門。它帶領出第一次針對電子樂器的作曲,與噪音製造器及其再衍生設備形成對比。1929年,約瑟夫·席林格創作了《特雷門與管弦樂團第一組曲》(First Airphonic Suite for Theremin and Orchestra),於克里夫蘭管弦樂團進行首演,並由李昂·特雷門擔任獨奏。 The decade brought with it a large number of early electronic music instruments, and the first time that Leningrad 除了特雷門之外,馬特諾音波琴於1928年由莫里斯·馬特諾發明,並在巴黎首次露面。[15] In addition to Tremendous, Matnoein posse was invented in 1928 by Maurice & Middot; Martano 隔年,喬治·安泰爾第一次為機械裝置、電子噪音製造器、馬達及擴音器作曲,應用於他未完成的歌劇《花先生》(Mr. Bloom)。 In the following year, wrote for the first time for mechanical devices, electronic noise makers, motors and amplifiers for his unfinished opera, Mr. Bloom. 錄音設備的發明使得電子音樂有了跳躍式的演進。1927年,美國發明家J·A·歐尼爾(J. A. O'Neill)利用在橡膠表面塗布一層磁性物質,開發了一種錄音裝置,然而在商業上卻失敗了。兩年後,勞倫斯·漢門為製造電子樂器而建立了他自己的公司。他繼續製造漢門式電風琴,這是基於特雷門的原理,並伴隨包括早期迴響裝置等其他發明[16]。漢門與約翰·漢那特(John Hanert)、C·N·威廉斯(C. N. Williams)繼續合作開發其它電子樂器,例如諾瓦合音琴是由漢門的公司於1939至1942年間製造。[17] In 1927, the American inventor J· A· J.A. O'Neill developed a recording device using a layer of magnets on rubber surfaces, but failed in business. Two years later, Lawrence & Middot; Hanmen

用於電影藝術上的光學聲音紀錄方法讓聲音的影像可視化變為可能,除此以外也領悟到另一面—從一人造的聲音波形來合成聲音。在同一時期,聽覺藝術實驗開始進行,早期的參與者有崔斯坦·查拉、柯特·希维特斯及菲利波·托馬索·馬里內蒂等人。

In addition to making visualization of sound possible by means of optical sound recording in film art, a different dimension has been learned - synthesizing sound from a man-made wave. During the same period, experiments were started with early participants: , Court & Middot; and et al.

; El-Daba at the Cleveland carnival in 2009.

低傳真磁性鋼絲錄音大約從1900年就開始使用[18]。到了1930年代初期,電影工業開始轉換成基於光電池而開發的新型光學式聲音伴隨影片錄像系統[19]。大約在同一時期,德國電子公司AEG發展出第一套實用化錄音帶系統「磁音機」K-1,並於1935年8月在柏林國際廣播展發表[20]。磁帶比唱片在錄音技術上有更大的彈性,可以重新再錄,亦可以剪接。自此以後,磁帶被廣泛應用於收音機廣播及有聲電影。

At the beginning of the 1930s, the film industry began to switch to a new optical sound based on , developed with the video recording system >. At the same time, the film industry began to develop its first practical use of light cell , with the video recording system > >.

在第二次世界大战期間,瓦爾特·韋伯(Walter Weber)再發現並且應用了交流偏磁技術,該技術藉由加入一個聽不見的高頻音調,戲劇性地改善了磁性錄音的保真度。它將1941年份K4磁音機的頻率曲線延伸至10kHz,並且提昇動態範圍至60dB[21],超越當時所有已知的錄音系統[22]。

During World War II , Walter & Middot; Walter Weber discovered and applied magnetic technology that dramatically improved the authenticity of magnetic recording by adding an invisible high-frequency tune. It extended the frequency curve of K4 in 1941 to 10 kHz and referred to the range of dynamics to 60dB > beyond all known recording systems at that time

早在1942年,AEG就已經進行立體聲錄音的測試[23]。然而這些裝置和技術一直對德國以外地區保密,直到二次大戰結束,當時被捕獲的磁音式錄音機及數卷法本公司生產的氧化鐵錄音帶被傑克·穆林等人帶回美國[24]。後來Ampex公司就在這些錄音機及帶子的基礎上,發展出美國製造的第一部商業化專業帶式錄音機Model 200[25],並獲得藝人平·克勞斯貝的支持,而他也成為第一批將廣播節目及專業錄音室錄音複製在錄音帶上的藝人之一[26]。

In 1942, AEG began a stereo recording of was produced by Jack & Midot; Murin et. al. brought back >.

磁性錄音帶為音樂家、作曲家、製作人及工程師在聲音表現的能力上開拓了一個廣大的空間。錄音帶相對便宜而且非常可靠,它重製的保真性也比當時任何的聲音保存媒介更好。更重要的是,它提供如同電影膠卷般的操作可塑性,而不像唱片一樣死板。帶子可以在錄音或是播放期間減速、加速或甚至倒帶,因而常有著驚人的效果。它幾乎可以如同電影膠捲一般在實體上編輯,允許錄音裡不需要的段落被無縫的移除或置換;同樣地,其他來源的錄音帶段落可以被編輯進去。錄音帶也可以結合成無止盡的迴圈效果,也就是重複播放先錄好的素材。音效放大器以及混音設備可進一步擴展了錄音帶的表現能力,允許多重預錄各種聲音(現場聲音、演說或音樂),再加以混合並同時錄製到其他帶子,僅會有相當些微的保真度損失。其他預料之外的收穫是錄音機可以相對簡單地修改成迴音機,用來製作複雜而可控制的高品質回聲及混響效果(這些大部分不可能以機械方式達成)。

Magnetic tape has opened a wide range of spaces for sound. The tape is cheap and very reliable, and it recreates better than any sound at the time. More importantly, it provides plastics like a film, rather than a record dead board. The tape can slow down, accelerate or even reverse during the recording period, and thus has a surprising effect on the sound. It can almost be edited on the site, and it can be removed or replaced by an uninterruptible item; and the rest of the audio clips can be edited.

錄音帶的擴散最終導致了電子聲學錄音帶音樂的發展。第一個已知的例子是1944年由哈利姆·埃爾-達巴作曲的,當時他的身份是埃及開羅的一個學生[27]。他利用笨重的鋼絲錄音機錄製具有古老傳統的薩爾典禮,並在中東廣播電台錄音室使用混聲、回聲、電壓控制以及再錄製處理這素材。該成果命名為《薩爾的表達》(The Expression of Zaar),並於1944年在開羅的一個藝廊演出。雖然他以錄音帶為基礎所作成的初步實驗並未傳播到埃及以外地區,埃爾-達巴仍然以其後來在1950年代晚期於哥倫比亞-普林斯頓電子音樂中心所創作的電子音樂作品而廣為人知。[28]

The spread of the tape eventually led to the development of . The first known example is that in 1944, by , whose identity was nofollow' > > <27 > > > >. He used the stupid /a's old-fashioned

主条目:具體音樂

Main entry:

在此前不久,巴黎的作曲家也開始利用錄音帶來發展一種稱為具體音樂的新作曲技術。這項技術牽涉到將事先錄好的大自然與工業聲音的片段編輯在一起。[29]巴黎的第一個具體音樂片段是由皮耶·薛菲組合而成,他後來則與皮耶·亨利合作。 Shortly before, the composers of /a> also began to use the recording to develop a new musical technique called /a> The first specific piece of music in Paris was by Pier & Middot; Xuefi combined with & Middot; Henry later collaborated with >. 1948年10月5日,法國廣播公司(RDF)播送了作曲家皮耶·薛菲的作品《火車習作》(Etude aux chemins de fer)。這是《噪音的五項研究》(Cinq études de bruits)的第一個樂章,標誌了錄音室實際化與具體音樂(或聽覺藝術)的開始。[30]薛菲採用一部切割圓盤用的車床、四部錄音轉播機、一部四頻道混音機、濾波器、一間回音室以及一套可攜式錄音設備。在此後不久,亨利開始與薛菲合作,這個合作關係可能對電子音樂的方向有深刻而持久的影響。另一位薛菲的夥伴埃德加·瓦雷兹開始創作《沙漠》,一首為室內樂團與錄音帶創作的作品。錄音帶的部分在皮耶·薛菲的錄音室製作,並且之後在哥倫比亞大學作修訂。 On October 5, 1948, the first French broadcaster marked the beginning of audio studios, audio studios, audio studios and devices. > , marked the beginning of audio studios, audio studios, audio studios and audio-visual art. 1950年,薛菲在巴黎高等音樂師範學院舉行了具體音樂的第一次公開音樂會(非廣播)。「薛菲使用一套公共播放系統、好幾部錄音轉播機以及混音器。這個表演並不夠好,因為使用錄音轉播機創造現場綜合表演的手法從來沒有被做過。」[31]同年稍後,皮耶·亨利與薛菲共同創作了具體音樂的第一個主要作品《孤獨人交響樂》(Symphonie pour un homme seul)。1951年,由於世界潮流所趨,RTF(原RDF合併電視業務而成)在巴黎建立了第一個製作電子音樂的錄音室。同樣在1951年,薛菲與亨利為具體音樂與人聲創作了一部歌劇《奧菲斯》(Orpheus,希臘神話中彈豎琴的名手)。 In 1950, Xuefi held the first public concert (non-radio) of specific music at the . "Huefi used , several audio recorders and mixers. This performance was not good, because the RTF (formerly RDF) created the first music studio in Paris as a result of the use of the recording recorder to create a live performance of later in the year; Henry and Xuefi co-authored the first major piece of music, Symphonie pour un homme seul. 卡爾海因茲·史托克豪森在電子音樂錄音室WDR,德國科隆,1991 Karl Heinz & Middot; Storkhausen in the electronic music studio WDR, Cologne, Germany, 1991 卡爾海因茲·史托克豪森曾於1952年在薛菲的錄音室短暫工作過,之後多年都在WDR位於科隆的錄音室從事電子音樂工作。 ; Stokehausen worked briefly in the Xerfie studio in 1952, and many years later WDR worked in the /a. 1953年,NWDR在科隆正式設立廣播錄音室,後來成為全世界最有名的電子音樂錄音室。其實早在1950年該錄音室就已著手籌備,並在1951年就有產出作品並進行廣播。[32]該實驗室是威納·梅爾-艾普勒、羅伯特·貝爾(Robert Beyer)與赫伯持·艾默特(他成為第一個編輯者)等人的智慧結晶,不久又加入了卡爾海因茲·史托克豪森與哥特弗里德·邁可·寇尼格。梅爾-艾普勒曾於1949年在他的論文《電子發聲器:電子音樂與合成語音》(Elektronische Klangerzeugung: Elektronische Musik und Synthetische Sprache)中推想出完全以電子製作信號合成音樂的概念;在這方面,德國的電子音樂明確地與法國的具體音樂區分開來,因為具體音樂是使用實際聲音作為來源。[33] In 1953, NWDR officially set up a radio studio in Cologne, which became the world's most famous electronic music studio. In 1950, the studio was actually ready for production and broadcast in 1951. The lab is an intellectual crystal of Weiner and Mitdot; Mel-Epple ; Robert Beyer & ; Emmet (who is the first editor) <32 > > > > > >, and soon joined the idea of Kmidot > ; Stork Haul and > ; 「由於施托克豪森及卡赫尔的坐陣,該錄音室變成一年到頭參訪者絡繹不絕、極富魅力的前衛大本營。」[34]這是在兩次結合電子產出聲音與傳統管弦樂團的作品——《混合》(1964年)與 《讚美詩,第三區與管弦樂團》(1967年)發表後所獲得的評價。[35]史托克豪森表示他的聽眾反應說他的電子音樂帶給他們一個「外太空」的體驗、飛行的感覺或是感覺身處「奇幻夢境」。[36]最近,史托克豪森改在他位於屈爾滕的私人錄音室製作電子音樂,他的最新作品在傳媒中叫做《宇宙脈動》(2007年)。 The sound studio became a year-long, glamorous former David base camp from and from by . [34] is an assessment of the sound and traditions of two combined electrons > > > > > > >. 當早期的電子樂器例如馬特諾音波琴、特雷門與特勞烏特琴在第二次世界大戰前的日本仍極少為人所知時,當時的一些作曲家如柴田南雄就已經知道這些樂器。戰爭結束後好幾年,日本音樂家開始實驗電子音樂;在一些機構的贊助下,作曲家得以應用最新的聲音錄製及處理設備。這些努力展現亞洲音樂與新興潮流的融合,並且最終為日本在數十年後成為音樂科技發展的主宰者鋪設了一條道路。[37] When early electronic instruments such as , , 隨著電子公司索尼(當時稱為東京通信工業株式會社)於1946年的創建,兩位日本作曲家武滿徹與柴田南雄於1940年代晚期各自寫到關於電子科技製作音樂的可能應用。[38]在1948年,武滿徹構想出一項新科技,可以「在一個小而擁擠管子內,將噪音與協調的音樂旋律結合在一起。」此與同年度皮耶·薛菲的具體音樂概念頗為相似。當時武滿徹的構想並未受到注目,並持續了好幾年。1949年,柴田南雄提出「一種高性能樂器」,可以「合成任何類型的聲波」並且「非常容易操作」,他預測有了這種樂器,「音樂的情境將有突破性的改變」。[39]同年,索尼發展出磁帶錄音機G-Type,[40]它成為法庭及政府機關裡最受歡迎的錄音裝置,也導致索尼於1951年發表家庭用版本H-Type。[37] In the late 1940s, two Japanese composers, , wrote separately about the possible use of electronic technology for music. [38] (known as the Tokyo Communications Industries Institute at the time) created in 1946, two Japanese composers, , combined noise and tuned music in a small tube. > ; > > ; music > > ; 1950年,一群音樂家共同成立「實驗工坊」電子音樂工作室,使用Sony磁帶錄音機製作實驗性電子音樂。參與的音樂家有武滿徹、秋山邦晴及湯淺讓二等。Sony贊助該工作室,讓音樂家們得以接觸最新的音頻科技,同時也雇用武滿徹創作磁帶音樂來展示其磁帶錄音機,並舉辦音樂會。[41]該團體最早產出的電子磁帶音樂作品是《被束縛的女人》(日語:囚われの女)及《作品B》(Piece B),由秋山邦晴於1951年完成。[42]他們創作的許多電聲音樂錄音帶作品常被用於廣播、電影及劇場的配樂。他們也舉辦了一些音樂會,例如1953年的《實驗工作坊,第五次展示》,該場使用一部由Sony發展的自動投影機器,讓投影展示與錄製於錄音帶上的原聲音樂同步化變為可能;他們在Sony的工作室使用相同裝置製作了此場音樂會的錄音磁帶。這場音樂會伴隨著他們製作的實驗性電子聲學磁帶音樂,形同為那年稍後引進日本的具體音樂預作了準備。[43]除了實驗工坊以外,有幾位作曲家如芥川也寸志、富永三郎與深井史郎也於1952至1953年間進行了製作廣播聲效磁帶音樂的實驗。[40] In 1950, a group of musicians joined together to set up an electronic music studio at the Experimental Workshop, using the Sony Tape recorder to make experimental video music. The musicians involved were full-fledged, and . Sony supported the studio, allowing musicians to access the latest audio technology, and used the somong tape recorder to show their tape recorder and organize a concert. > > > 日本經由黛敏郎引進了具體音樂,他在1952年參與了薛菲在巴黎的音樂會。[42]回到日本以後,他為1952年的喜劇片《純情的卡門》實驗性製作了一個簡短的磁帶音樂作品,[44]並且製作了《X、Y、Z為具體音樂》,於1953年由日本文化放送(JOQR)電台播放。[42]黛敏郎也為三島由紀夫的1954年廣播劇《拳擊》製作了另一首具體音樂作品。[44]然而,薛菲的法國概念「聲音物件」並沒有影響到日本作曲家,取而代之的是他們的主要興趣——音樂科技,如同黛敏郎所言,克服「人類表現材料與範圍」的限制。[45]這導致了一些日本電聲音樂家使用序列主義和十二音技法於作品上,[45]例子有入野義朗的1951年十二音體系作品《照相機的音樂會》(意大利語:Concerto da Camera)、[44]黛敏郎的《X、Y、Z為具體音樂》及其後柴田南雄的1956年電子音樂作品。[46] When Japan returned to Japan by /a>, for the 1952 comedy film , for the pure Carmen experiment, which produced a short piece of tape music in 1952 at > Paris. 在建立於1953年的科隆錄音室引導下,日本NHK公司也於1954年在東京建立了電子音樂全球領先機構之一的「NHK錄音室」,配備有音調產生及音訊處理設備、錄音與聲光設備、馬特諾音波琴、單弦樂器以及旋律和弦發聲器、正弦波震盪器、帶式錄音機、鳴響調諧器、帶通濾波器及4通道與8通道混音器。該錄音室相關的音樂家有黛敏郎、柴田南雄、湯淺讓二、一柳慧以及武滿徹。錄音室的第一批電子音樂作品於1955年完成,包括黛敏郎使用錄音室的各種音調產生設備製作的5分鐘作品系列:《研習一:依質數比例的正弦波音樂》、《依依質數比例的協調波音樂》及《方波與鋸齒波的發明》,以及柴田南雄的20分鐘立體聲作品《為立體聲廣播的具體音樂》。[47][48] Japan's NHK company, led by the Cologne studio established in 1953, also established the `NHK studio', one of the global leading electronic music institutions in Tokyo in 1954 at , equipped with audio-recording and audio-processing devices, recording and audio-visual devices, Matno-sonics, strings, and , `sythonics', phonophones, symphonics, 在電子樂器製造方面,梯郁太郎於1940年代晚期成立了一個「梯錶店」修理工坊,專門修理手錶跟收音機;其後於1954年成立「梯無線」。它在1960年發展成為專門製造電子音樂設備的王牌電子工業公司,並且在1972年成為樂蘭公司。梯郁太郎於1955年開始製作電子樂器,目標是創造能產生單聲部旋律的設備。1950年代晚期,他製造特雷門、馬特諾音波琴及電子琴,並且在1959年製作出夏威夷吉他放大器與電子風琴。[49] In the field of electronic music production, Etonyro set up in the late 1940s a shop to repair watch shops and radios; then in 1954 it set up the Lading Wireless. the Acetic Industries , and in 1972 it became . In 1955 it began to produce electric instrument designed to create a single-sounding rhythm. 在美國,電子音樂早在1939年便已被創造出來,當時約翰·凱吉發表了《想像的風景》,使用兩部可變速的唱機轉盤、頻率錄音機、無聲鋼琴及鐃拔。凱吉於1942至1952年間又陸續創作了另外四首《想像的風景》系列作品,全部都包含了電子元素。1951年,後來與凱吉合作的莫頓·費爾德曼創作了一首名為《邊緣交叉》的作品,以風聲、銅管樂器、敲擊樂器、弦樂器、兩個震盪器及極有吸引力的音效譜寫,並且搭配費爾德曼的圖解。 In the United States, electronic music was created as early as 1939, when Caggie published the picture , using two variable-speed singers, video recorders, silent pianos, and thugs. Kaji produced four more series of "The Vision" from 1942 to 1952, all of which contain electronic elements. In 1951, Morton & Midot, in collaboration with Cage, Feldman wrote a book called "The Margin Crossing", written by wind, brass tubes, beaters, stringers, two seismographs, and extremely attractive syntheses, and co-written with Federman. 「磁帶音樂計畫」是由紐約學校的成員(約翰·凱吉、厄爾·布朗、克利斯提安·沃爾夫、大衛·德鐸及莫頓·費爾德曼)創建,[50]並且維持了3年,直到1954年才結束。凱吉為這個合作寫到:「在這個黑暗的社會裡,然而厄爾·布朗、莫頓·費爾德曼及克利斯提安·沃爾夫的作品持續展示了智慧的光亮,為一些觀點作註解、表演以及試聽,此一行動是刺激的。」[51] The Tape Music Project was created by members of (John & Middot; Kaj; Earl & Middot; Brown, Krystien & Middot; Wolf , and Morton & Middot; Feldman) ; Brown, Morton & Middot; Feldman & Klestimandandot" [50] /a /a /l /l /l /l /l /l /l /l /l / / / / /l / / /l / / /l / / / / / / / / / / /l / / / / /l / / / / /l / / / / / /l / / / / / /l / / / / / /l / / / / / / / / / / / /f /f /f /f /f / /f / / / / /f / / / / / / / /f / / / / / / / / / /f / / / / / / / / / / / / 凱吉於1953年完成了《威廉姆斯混音》,當時他於為「磁帶音樂計畫」工作。[52]這個團體沒有固定的機構,必須依賴向商業聲音錄音室借用時段,包括貝貝與路易斯·貝隆錄音室。 In 1953, Kaji completed "a rel="noformlow" Williams mix

同年,哥倫比亞大學為了音樂會的錄音,購買第一套帶式錄音機——一套專業的Ampex機器。弗拉基米爾·烏薩切夫斯基當時在哥倫比亞大學音樂系負責這個裝置,並且幾乎立刻開始對它進行實驗。

In the same year, Columbia University purchased the first set of tape recorders -- a specialized set of Appex machines. /a> was in charge of the device at the Columbia University Music Department and almost immediately started experimenting on it.

赫伯特·盧斯柯爾(Herbert Russcol)寫到:「不久他被這套可以自行達成的聲響迷住了,藉由錄下樂器聲音,並且之後將它們互相重疊。」[53]烏薩切夫斯基之後說道:「我意外地領悟到錄音機可以被視為一個聲音轉變的儀器。」[53]1952年5月8日,在哥倫比亞大學麥克米林(McMillin)劇院裡,烏薩切夫斯基於他所創立的作曲家論壇中呈現了數種錄音帶音樂及他製作的音效展示。該次展示包含了變調、迴響、實驗、組合以及水下華爾滋。在一次訪談中,他說道:「在紐約的公開音樂會中,我呈現了一些我發現的例子,伴隨著我曾經為傳統樂器所創作的樂曲。」[53]奧托·呂寧參與了這場音樂會,他記錄:「他所配置的設備包含一部Ampex磁帶錄音機……及由年輕的天才工程師彼得·冒齊(Peter Mauzey)所設計的一個簡單盒狀裝置,用來創造一種機械式迴聲形式的回饋效果。其他設備是借來的或以個人資金購買的。」[54]

[Herbert & Middot; [Herbert Russcol] wrote: "He was caught in the sound that he could make on his own shortly, by recording the music, and then regressing it." Usachevsky said: "I unexpectedly learned that the recorder could be seen as a voice-shifting instrument." May 8, 1952, in the University of Colombia McMillin, "Usachevski" in his captions, I found several audio-telephones and his olremut/remotes.

就在3個月後的1952年8月,烏薩切夫斯基在呂寧的邀請下,前往佛蒙特州本寧頓展示他的實驗。在那裏,兩人合作創造出各式各樣的作品。呂寧描述這件事:「備有耳機以及一支長笛,我展開了自己的第一次磁帶錄音機作曲。我們彼此都是熟練的即席演奏者,而這個媒介點燃了我們的想像。」[54]他們在一場非正式的派對上表演了一些早期作品,在那裏「一群作曲家相當慎重地恭喜我們說:『就是這個』(『這個』指的是未來的音樂)。」[54]

Just three months later, in August 1952, Usachevsky, at the invitation of Linning, went to Vermont they performed some early work at an informal party where "a group of composers were very cautiously congratulating us that this is the song of the future" [54].

消息很快就傳到了紐約市。奧利佛·丹尼爾(Oliver Daniel)打電話邀請兩人「為美國作曲家聯盟及廣播音樂公司贊助,由李奧波德·史托考夫斯基指揮,在紐約現代藝術博物館舉辦的十月音樂會創作一些簡短的作品。在一陣猶豫之後,我們同意了……亨利·考埃爾安排他位於紐約州伍德斯托克的住家及錄音室,以供我們使用。我們用烏薩切夫斯基車子的後行李箱放置借來的設備,便離開本寧頓前往伍德斯托克,並在那裡停留兩個星期……1952年9月末,這間移動實驗室抵達了烏薩切夫斯基位於紐約的房間,在那裏我們終於完成了這些作品。」[54]

The news quickly spread to New York City . Oliver & Middot; Oliver Daniel called to invite two people to "co-sponsorship for the American Companion League and the Broadcasting Music Company" by , directed to make short works at the October concert at the modern art museum in New York City. After a while of hesitation, we agreed to leave Bennington for Woodstock and spend two weeks there.

注册有任何问题请添加 微信:MVIP619 拉你进入群

打开微信扫一扫

添加客服

进入交流群

1.本站遵循行业规范,任何转载的稿件都会明确标注作者和来源;2.本站的原创文章,请转载时务必注明文章作者和来源,不尊重原创的行为我们将追究责任;3.作者投稿可能会经我们编辑修改或补充。

HackSnake

HackSnake